Miniatures for Hertl

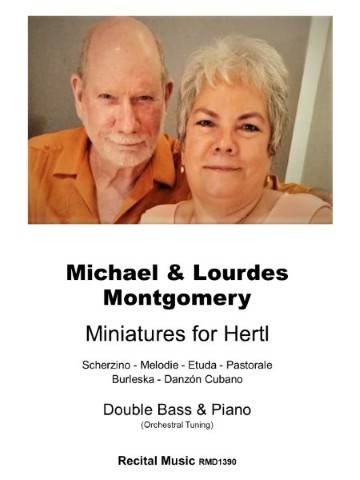

Composer: Michael and Lourdes Montgomery

Instrumentation: Double Bass and Piano

Publisher Recital Music

Miniatures for Hertl includes six colourful and engaging pieces for the intermediate bassist, five by Michael Montgomery and one by Lourdes Montgomery. The pieces can…

Page ? of ?

Digital Download – PDF

Shipping costs: No shipping

R.R.P £8.50

Our Price: £7.23