Your basket is currently empty!

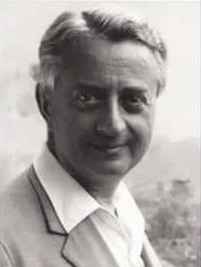

The Fascinating Life of Karel Reiner

Sonata for double bass & piano

“Karel Reiner (1910–79) – a major missing voice in Czech music – suffered under both of twentieth-century Europe’s major tyrannies. As a Jew he was imprisoned by the Nazis, miraculously surviving a series of atrocities: Terezín, Auschwitz, a camp near Dachau and a death march. Then, back in Prague after the War, he was accused of ‘formalism’ by the Communists.”

Karel Reiner was born on 27 June 1910 in the small town of Žatec (Bohemia) into a middle class Jewish family. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatoire with Josef Suk, alongside theory and quarter-tone composition with Alois Hába – a pioneer of new musical trends. Reiner was much sought after to play Hába’s specially built quarter-tone piano and performed his final examination piece (Piano Sonata No.1) at the Vienna Contemporary Music Festival in 1932. He continued to compose, including music for the influential avant-garde theatre in Prague, but after the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1938, he was unable to perform or publish any of his music.

However, his works were played at many ‘underground’ concerts and the compositions continued to be written. From the middle of 1943 to September 1944 Reiner was a prisoner in Terezín (Theresienstadt) concentration camp, close to Prague. He was allowed to give concerts, played much contemporary music and also gave many music lessons, alongside writing theatre music for children and adults. In September 1944 he was sent from Terezín to the Auschwitz death camp, and then to Dachau, surviving a deadly typhus epidemic in Dachau, and he was the only Jewish composer to survive the atrocities of the Second World War.

Reiner returned to Prague and believed that his music should now communicate and be available to everyone. Between 1950-54 his work slowly changed and evolved and he successfully combined traditional composition with contemporary musical expression. After the end of the war Reiner joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and composed a number of political songs, which didn’t meet the expectations of the Party. Doris Grozdanovičová, a fellow Terezín inmate, remembers “…He met increasing resistance from the authorities: his style was too individualistic, too ‘formalist’, it didn’t conform with socialist prescriptions…And so he fell into a kind of isolation that had considerable consequences for his music…I think that the tragedy which explains why Reiner has remained unknown has to do above all with the fact that political developments meant that he couldn’t be played in public any more. His musical language was largely rejected by the authorities and so there were only a very few performances…In the aftermath of the ‘Prague Spring, he left the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in 1970 and had to renounce all his official positions and performances of his music were banned.”

Karel Reiner was a prolific composer, was liked by the musicians he worked with, wrote in almost every genre, and his music is certainly worthy of revival in the 21st-century. He died in Prague on 17 February 1979. Reiner’s Sonata for double bass and piano dates from 1958 and was published by Panton (Prague) a year later. It is dedicated to Professor František Hertl, one of the most important and active Czech bassists of the time, and is in three movements. Reiner decided to write a work for an instrument which didn’t have a huge repertoire and the result is a great work of enormous contrasts and breadth. Although the composer may not have been a double bassist, the solo line fits the instrument remarkably well and it is possible that Hertl, or another Czech bassist, helped with the technical aspects of the work. The three contrasting movements demonstrate a composer with an excellent knowledge of the capabilities and limitations of the double bass, is in a modern idiom, but is always lyrical and expressive. It was out or print for many years before Recital Music prepared a new edition in 2003, with the approval and help of the composer’s widow, Mrs Hana Reinerová, and it was reviewed soon after by Double Bassist magazine: “Karel Reiner’s Sonata for Double Bass and Piano (1958) opens in an aggressive and intensive way which immediately grabs the listener’s attention. The piece is full of strident dissonances; the bassist playing at full or near-full volume over a harmonically ambiguous piano accompaniment. While the piece is largely tonal, this tonality is constantly threatened by pungent semitones that populate its thematic material. Indeed, the strong presence of tonic and dominant relationships throws these contrasting dissonances into sharp relief. Those who know the Expressionist music of Alban Berg will find themselves on familiar ground here: this piece was written by a Holocaust survivor and the work’s ominous, dark atmosphere – full of shrill yet lyrical writing, dissonance and tonal ambiguity – seem to speak of the pain and anguish of the human condition rather than its triumphs. Technically, this is a very comfortable piece to play because most of the melodic material is based on thirds (particularly minor) and semitones, with few large leaps. The three movements vary significantly from one another: in the mournful second movement, marked Poco grave, the accompaniment explores various keys, which are constantly undermined and resisted by the double bass as it meanders around a semitone melody. Amid the tension created by this conflict, major and minor triads emerge dramatically. According to the notes accompanying the music, the third movement, Allegro vivo, is based on a Czech dance. While the harmonic language does not particularly lend itself to creating the sound of a joyful dance, this movement nevertheless has a spirited energy and concludes on the chord of B major. This is an interesting addition to the double bass repertoire; whether modern audiences will appreciate its brash and unremitting dissonance is open to debate.”

American bassist, Michael Cameron, who has an excellent and exciting project to promote, perform and commission sonatas for double bass places Reiner’s Sonata as “…one of the top ten double bass sonatas in any period.” – with which I completely agree. He disagrees with some of Double Bassist’s review, especially the words “brash and unremitting dissonance” and writes “…this is hogwash. While not exactly a sunny piece, it is consistently tonal, and often quite lyrical.” Michael Cameron understands the work completely, which I am not sure the reviewer did, and its use of tonality and atonality, always within a lyrical and melodic approach, produces a modern piece which is accessible to players and audiences alike.

Much like the Hindemith Sonata, the performance is dependent on the approach of the double bassist who is able to bring out the warm lyricism of both works or their more strident and acerbic qualities. The outer movements have great drive and energy, with a slow and passionate central movement which feels almost like a funeral march. The first movement (Allegro energico) is grand and confident with an opening theme of heroic quality and sets the tone for the movement. Both performers begin together, there is no piano introduction, and Reiner sets the dramatic and urgent mood immediately. The accompaniment is broad and imposing – sometimes a wash of colour and texture and at other times with a rhythmic impetus which drives the music along – and the composer makes effective use of the lower orchestral register, producing music which is richly dramatic and inventive. The slow movement (Poco grave) makes use of a chromatic influenced melody, again with no piano introduction, and creates an opportunity for the double bassist to sing in all registers and demonstrate far more than simply technical prowess. The opening theme is described as “…an aching lament expressing human sadness” in the text from the first edition of the work, and offers much to the bassist who can produce a warm and cantabile tone throughout the range of the instrument. The third movement (Allegro vivo) is different again. “… in a scherzo form and is in reality the finale of the whole composition. It’s musical expression, recalling in places the Czech “mateník” (an old Czech dance in variable time), is full of humour, both impetuous and playful. The lyrical contrasts give a picture of repose and relief. The basic character of the movement is its energetic humour…” There are many challenges for the bassist, both musical and technical, and the movement has a drive and momentum from beginning to end. The contrast of powerful and urgent rhythmic themes against lyrical and expressive episodes produces music of enormous breadth and appeal. Reiner takes his task seriously and the end result is a contemporary work which explores many facets of the solo double bass in all its glory. Both the musical and technical skills of the performer are challenged, producing a work which deserves to be better known, and although it has been recorded at least twice, it is still somewhat in the shadow of the Hertl, Hindemith and Mišek sonatas. Each composer offers the performer something different and possibly Reiner’s musical language is less obvious than the others, but is still a work which is worth exploring and should appeal to the serious double bassist, offering much to performers and audiences alike. I completely agree with Michael Cameron and think Karel Reiner’s Sonata is definitely in the top ten of sonatas from any period. How about you?

Karel Reiner’s Sonata for double bass and piano will be available as a digital edition from Recital Music towards the end of 2025.

David Heyes. March 2025.

Picture courtesy of David Heyes. Gifted to him by Hana, the widow of Karel Reiner.

Discover more from The Music Realm

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.