The history of the double bass has always held an enormous fascination for me, especially the players, teachers and composers, and over the past 40 years I have enjoyed rediscovering overlooked, long forgotten or unknown works. Each piece of music is part of the rich double bass heritage, every composer has made a unique contribution whether large or small, and the double bass world is where it is today thanks to the great work and pioneering endeavour of so many bassists. I enjoy finding neglected composers and repertoire and giving each a helping hand by writing about them or preparing new performing editions for the 21st-century.

Over the past 40 years I have commissioned more than 700 original works for double bass, from one to twenty basses, and from complete beginner to virtuoso. It has been an absolute pleasure to work with so many wonderful composers but that part of my life, for now, is on hold and my plan over the next ten years is to devote my time to increasing and developing repertoire for the beginner bassist and also to creating new editions of music from the past. The names of JP Waud and James Haydn Waud have long been consigned to the archives, known only by a few diehard bass nerds like myself, and Recital Music [www.recitalmusic.net] has one publication by each of them in its catalogue.

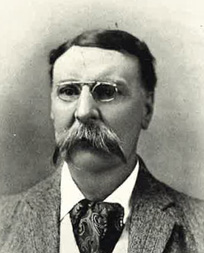

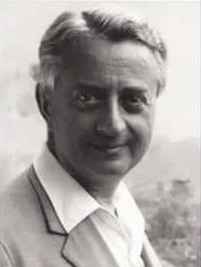

James Haydn Waud is the more eminent of the two, with an article about his life in The Strad, alongside a wonderful photograph of him sporting a walrus moustache, which would have been the fashion of the day. James Haydn Waud was the nephew of JP Waud and, thanks to the internet and a gift from a friend in Canada, I have been able to unearth more information about the uncle.

Joseph Pritchard Waud was born in Chelsea (London) on 30 July 1833 and in the 1861 census he was 26 years old and described as ‘proffesser of music’, but in later census entries he was a ‘teacher of music’. He married Eliza Walford in 1858 and the disparity in age between husband and wife, taken from each census, ranges from two or four to seven years. They had three children, a son who died at the age of four or five, and two daughters who also became music teachers. JP Waud’s biography on a family tree website states: “He performed on the pianoforte, double bass and violincello, is engaged at the Crystal Palace in the permanent band of the company also at the Theatre Royal Haymarket, and at various concerts. He also has private teaching. He lived at 306 King Street, West Fulham (renamed from 9 Grove Place in 1884)…” Joseph Pritchard Waud died on 7 July 1905 in Hove, West Sussex at the age of 71 and his will states that he left “all his money in his Post Office Savings Bank, all his land at Caterham Surrey and two double basses now in possession of nephew James Haydn Waud…” to his youngest daughter Miriam Priscilla Waud, described as a spinster.

All very ordinary and nothing much of interest apart from being the composer of a Progressive Tutor for the Double Bass which was published in about 1895 by Augener & Co. (18 Great Marlborough St, London). I produced a volume of 30 studies from the Tutor some years ago but knew very little about the composer until now, thanks to a gift from my friend Wilmer (Bill) Fawcett. Bill and I have corresponded by email for a few years, recently about the music of Max Dauthage, and he mentioned that he had some music by JP Waud, and asked if would I like the copy? Of course I said yes, particularly because it was something I didn’t have but also knew nothing about.

The package arrived a few weeks later and included two pieces by Othmar Klose alongside 6 Solo Studies for the Double Bass with Pianoforte Accompaniment by JP Waud. There is no publication date and the only clue to the publisher is ‘S.E.E. 321’, which sadly doesn’t mean anything to me, but my bass history appetite was whetted. The six pieces look very playable, with simple and supportive accompaniments, and it will be nice to bring them back into print over a century after they were first published. They are a similar ability level to the Eccles Sonata, primarily in bass clef, but venturing into thumb position, and would be ideal for the progressing bassist who is starting to play in low thumb position.

Having searched the internet today I found more information about JP Waud and discovered that there are also two pieces for ‘Contra Bass (Double Bass) and Piano’, also arranged for cello, and four books of studies for violin or cello and piano. An Adagio in C and Andantino in A feature a description ‘These are within the capabilities of any ordinary double bass player; will be found very useful for practice; are excellent for teaching purposes; and well adapted for Concert Solos.’ They were published by Haynes & Co. (14 Gray’s Inn Rd, London), advertised in the June 1896 edition of ‘Strings: The Fiddler’s Magazine’, and it’s the first time I have found any information about JP Waud or his music.

I contacted The British Library, who were very helpful but didn’t have a copy of either piece, so my journey begins today. The publisher no longer exists and where to start my search? The one thing I know is that patience is the key and it’s amazing how many pieces of music have surfaced in recent years, thanks to internet friends across the world. I’ll start looking, keep asking fellow bassists, and I am certain that copies will eventually be found.

Are any of these long lost masterpieces? I doubt it or they wouldn’t have been forgotten, but they are still interesting footnotes in the development and history of the double bass in the UK at the end of the 19th-century. It would be nice to create new versions for the 21st-century and copies will be sent to The British Library, alongside many other national and international libraries, so that the music is available for future generations.

David Heyes

April 2025

Recital Music Publications containing works by J.P Waud and J.H. Waud can be found here: